Future buildings will be highly insulated and heated with renewable energy. The systems will be fully integrated, connected to the grid and operate to continuously optimise for occupant comfort wile minimising emissions… but who’s going to pay for them in the long run?

Climate neutrality creates a challenging future for residential housing…

The climate-neutral buildings of 2050 will be highly insulated and heated by heat pumps that run on renewable electricity. While it is relatively easy to build these from scratch, the vast majority of the British building stock has to be converted into climate-neutral buildings.

Either way, it won’t be cheap: the average cost of an energy efficiency retrofit and the electrification of a domestic heating system in the UK sits between £ 15,000 and £ 20,000, a handsome sum! Fortunately, this isn’t the whole story. Efficient buildings require very little energy – the energy costs decrease and living comfort increases because of efficiency improvements. The efficiency investment can pay off within years.

… but technology may help

Save the climate and save money? Sure, why not. How about making some money too? Well, in the carbon-free future, once our electricity is primarily generated by wind and sun, there will be a high demand for energy flexibility services, which technology enabled buildings can contribute to and earn money from. These innovative buildings will therefore outperform purely climate-neutral buildings.

Is someone going to invest?

Owner-occupiers (two thirds of Britons) will ultimately receive these gains once they have made the initial investment to improve their buildings energy efficiency. But 4% of owner-occupiers move every year and a third of UK homes are rented.

Would you be willing to spend money on a more efficient home if it’s going to benefit a later owner or a tenant, unless that affects the price you can get for the building?

The present shows: yes, with markets’ help …

First of all, one would expect that energy cost savings would increase the building selling price to the same extent. For example, savings of £800 per year in energy costs would add £8,000 to the price of a building over 10 years – interest-free for simplicity. If the price rose by less – say £7,000 – buyers would be faced with the choice of either buying the efficient building for a premium of £7,000 and saving 10x £ 800 in energy costs, i.e., an expected profit of £ 1,000, or buying the less efficient building without any premium. Both buildings would only be traded if the premium equals future savings.

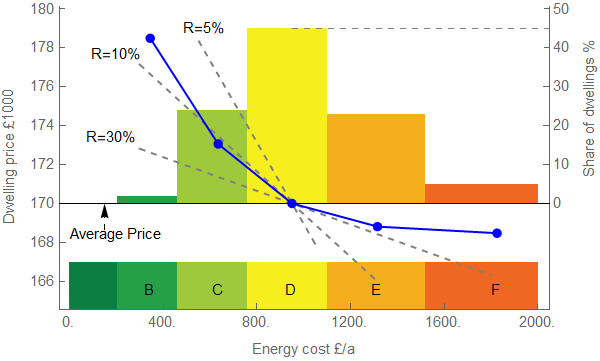

But it’s not that simple. It is true that empirical analyses show that investments in building efficiency are already generating far higher returns on real estate markets than on the capital market: An efficient (SAP B-rated) building – which is far less efficient than a building that also generates revenue through grid flexibility services – is 8% more expensive than an average (D-rated) building as it saves half the energy bill (figure 1).

… it may be even more!

However, buyers differ in terms of their discounting and their preferences for properties, for example a blue entrance door of a Notting Hill house. Far-sighted buyers then compete for the few particularly efficient buildings and drive up their price – beyond the value of energy savings. A pending study (watch this space) suggests that under these circumstances the market price “includes” more than 75% of future energy savings.

This raises hopes!

We haven’t said anything about the return on investment yet, as after all, the potential savings still have to cover investment costs – but that’s another topic.

However, it is gratifying to see that even today – with low earning opportunities – markets already value energy efficiency measures. This largely sustains incentives to improve efficiency – not a matter of course given the complexity of the topic, the uncertainties involved and the non-professionality of the “investors”.

Dr. Joachim Geske is an energy economist. He entered his current position at the Department of Management at Imperial College Business School, Imperial College London, in September 2015. He contributes to the Active Building Centre Research Programme with economic analyses of business models.