No one wants to go back to normal after this, certainly not in terms of the lack of investment in the environment, anyway. If we do, we’re all screwed. ‘Build Back Better,’ has almost overnight become the new mantra for redressing the imbalanced approach to the economy leading up to 23 March 2020, the day the coronavirus changed all our lives forever. Even the energy firms agree: earlier this month, Energy UK and PwC released their report Rebuilding the UK economy: fairer, cleaner, more resilient, highlighting 5 key areas for change as we return to an uncertain future. One of these is a push toward the comprehensive electrification of our transportation sector, and our researchers have been modelling this adoption and have calculated the financial benefit to our energy network to be upwards of £5 billion every year.

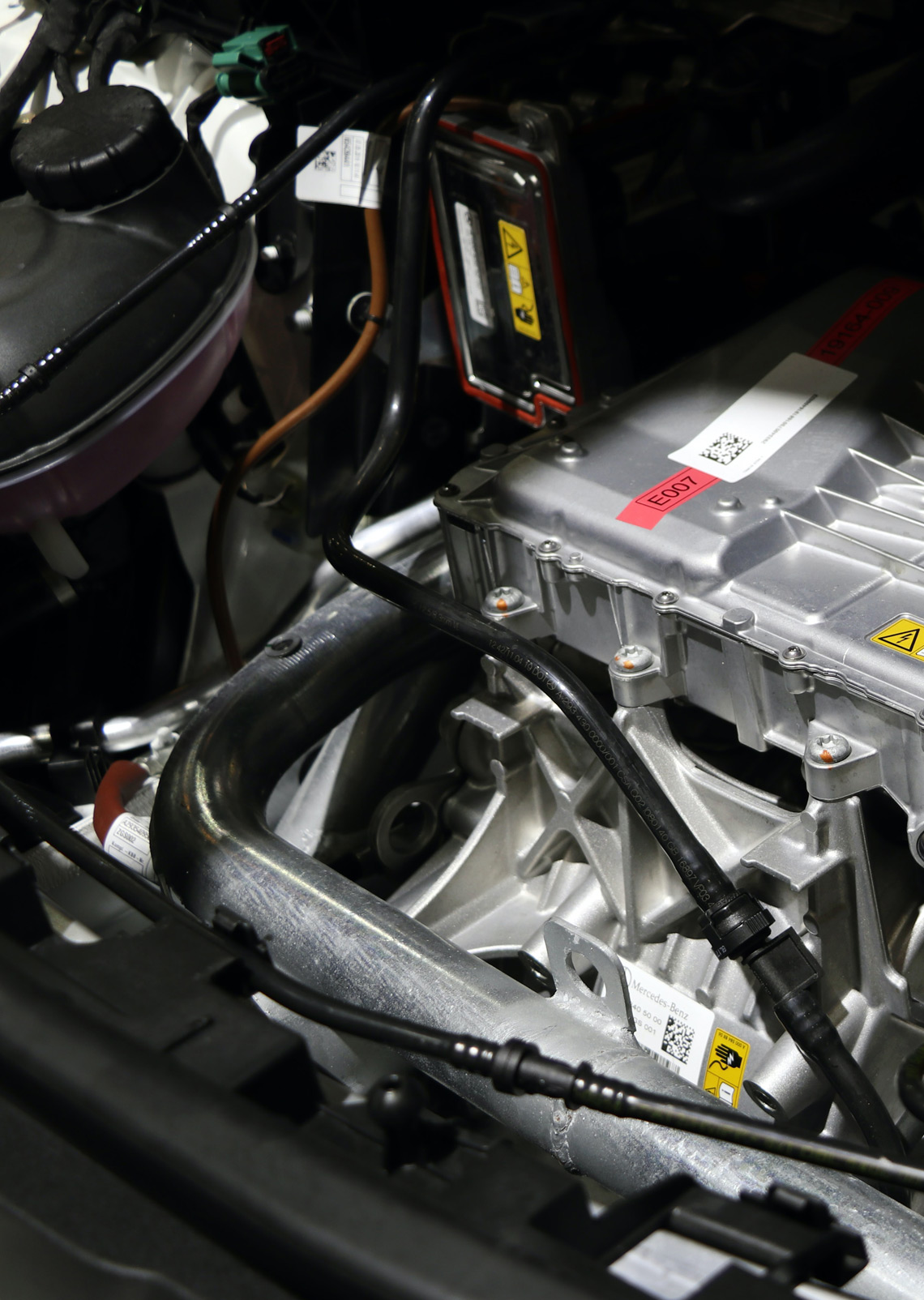

Vehicles powering things other than themselves (V2B or V2G) isn’t new, well, not globally anyway. Japan was the first to it, back in 2013, powering an office building off 6 cars during peak demand. It took the UK (only!) 7 more years to catch up, but as of May 2020, cars are now powering city hall in Islington. Currently in the UK predominantly Nissan vehicles offer such flexibility, but other companies such as BMW, Volkswagen and Honda are heading in that direction. Tesla, the ever-present elephant-in-the-room, seems to have pinned its future on its PowerWalls instead of car batteries, as a recent report its cars were V2G-ready was quickly and swiftly debunked. Regardless, as EV numbers continue to increase, and with the UK government promising all new cars to be fully electric within the next 12 years, our charging infrastructure has to adapt, and this will include our buildings by extension.

With cars being largely stationary throughout their lives, having a car battery as a direct power source for a building has its advantages: it’s stable (reducing the risk of surges or outages), it’s local (reducing system losses), it’s reliable (well, up to the point it hits empty), and it’s rechargeable. Taking buildings off-grid and on-car can net an EV owner up to £400/yr. This may not seem like a pot of gold (considering the average price of new EVs in 2020 according to my shiny new Wired magazine is £61k), but as EDF underlines, it is enough to provide free fuel for over 8000 miles, which for an EV owner is basically no bills, the same business model sweeping new house build schemes in Wales.

Our modellers at Imperial College London on the Active Building Centre Research Programme have estimated electric vehicles with V2G flexibility will have an annual benefit to the electricity network of between £5-£8 billion pounds per year by 2050, through the offsetting of energy infrastructure investment due to the availability of direct-connection of our houses to our cars (their recent report to the Committee on Climate Change can be downloaded here.)

Other researchers at our partner University of Nottingham have begun to model how many cars would be near enough to a V2G charger when stationary; their equations include using the radius of the earth, which is pretty cool, and their findings indicate over 92% of cars are parked close enough to a charging point when stationary.

Yes, you will be driving an EV eventually, and yes, its power will extend beyond its four wheels and into your kettle. The Active Building Centre Research Programme is pioneering technology to marry transport and buildings. Get in touch if you’d like to hear more.